Keith Ransom-Kehler

Keith Ransom-Kehler

Born:February 14, 1876

Death: October 23, 1933

Place of Birth: Dayton, Kentucky

Location of Death: Isfahan, Iran

Burial Location: Bahá’í cemetery near the graves of two distinguished brothers, Mírzá Muhammad Hasan and Mírzá Muhammad Husayn, King of Martyrs and the Beloved of Martyrs

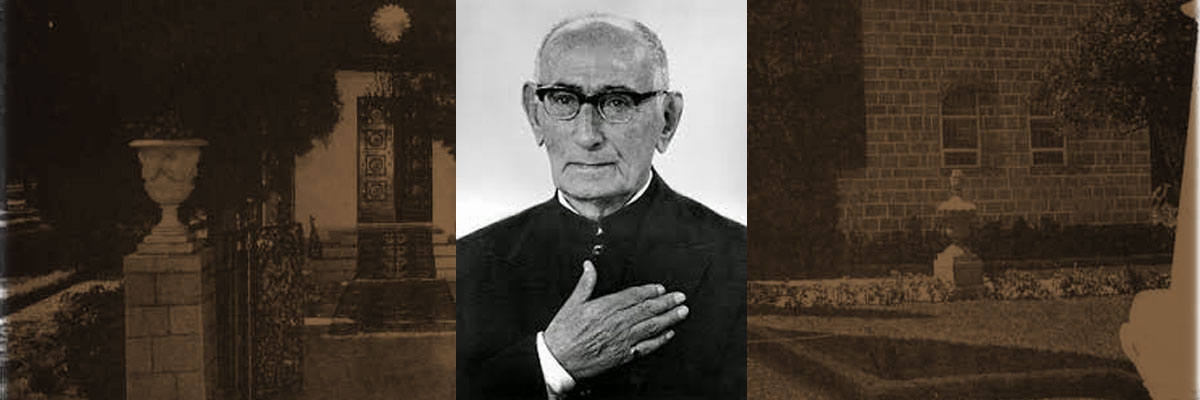

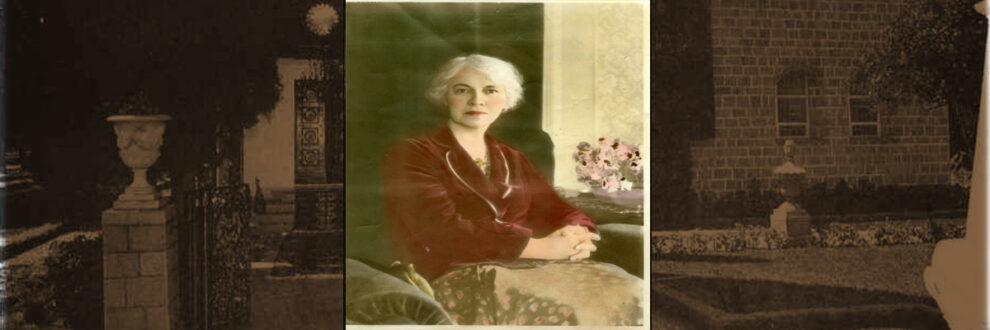

American Bahá’í lecturer and world traveler; designated by Shoghi Effendi as the first American Bahá’í martyr and, posthumously, a Hand of the Cause of God, the first woman to be so named.

Keith Ransom-Kehler was born Nannie Keith Bean in Dayton, Kentucky, across the Ohio River from the city of Cincinnati, Ohio, on February 14, 1876. Her parents were William Worth Bean, who used the courtesy title “Colonel” often adopted by descendants of Confederate officers, and Julia Bean (neé Julia Belle Keith). Nannie Keith, who came to be known solely by the family name Keith, had a younger brother, William Worth Bean Jr. (b. 1880). The family lived in the Cincinnati area, where from 1880 to 1889 Colonel Bean owned a horse-drawn rail line that ran on the Kentucky side of the Ohio River. Keith received her early education at the Bartholomew English and Classical School for Girls in Cincinnati and later attended Miss Grant’s School in Chicago.

In 1889 Keith’s parents and maternal grandparents moved to the Saint Joseph–Benton Harbor area of southwestern Michigan, where her father and grandfather were among a group that bought the streetcar system. Shortly thereafter, Colonel Bean formed the company that brought electricity to the twin cities less than ten years after the invention of the electric light bulb. His pioneering ventures caused him to be recognized as one of the area’s leading citizens.

Keith Bean attended Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, an outstanding tertiary educational institution for women, and received a bachelor’s degree in child psychology in 1898. In 1901, at the age of twenty-five, she married Ralph Ransom, a young painter from Saint Joseph who had attended the Art Institute of Chicago. She spent some time with him in Paris, where he studied with the influential American painter and etcher James McNeill Whistler, completing his studies at the Académie Delecluse in Paris in 1906. Meanwhile, Keith Ransom continued to pursue her own interests. Her file at Vassar College indicates that she attended Albion College in Michigan in 1903–04, earning a master’s degree in 1904, and then taught English literature there in 1904–05; she also studied at the University of Michigan (1904), the University of Arizona (1907), and the University of Chicago (1910). On 11 February 1907 she gave birth to a daughter, Julia Keith Ransom. A little over a year later, on June 5, 1908, Ralph Ransom died, apparently of tuberculosis. His mother, Mary Ransom, who lived in Saint Joseph, appears to have played a role in raising young Julia when Keith Ransom was traveling (to Europe with her father, for example, in 1908–09), studying, or working in Chicago.

In October 1910 Keith Ransom married James Howard Kehler, a successful and innovative advertising executive with an office on Michigan Avenue in Chicago. She retained and hyphenated her married names, thus becoming known as Keith Ransom-Kehler. In 1913 she gave birth to a stillborn infant. The couple had no other children together. Jim Kehler, who was divorced, had three offspring from a previous marriage: two sons, Stewart and Gordon, and a daughter, Elizabeth (who married Robert Llewellyn Wright, youngest child of Frank Lloyd Wright and Catherine Wright, in July 1933).

James Kehler and Keith Ransom-Kehler enjoyed a high social position in Chicago and friendships with such people as the architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Ransom-Kehler also had an association with Jane Addams, founder of Hull House and of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, established in 1915, of which Ransom-Kehler was a member. In 1914, she became a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution, tracing her ancestry back to her maternal great-great-grandfather, a captain in the Revolutionary War.

Well-educated and independent of spirit, during her two marriages Ransom-Kehler settled into neither domesticity nor a conventional career. In addition to teaching at Albion College, at various times she ran an antique shop, a tearoom, and a chicken and fruit farm, and, after taking a course in design, served as chief consultant for the interior decoration section of the Carson Pirie Scott department store in Chicago. From 1918 to 1922 she led the Liberal Religious Fellowship in the Chicago area. She divided her time between Chicago and Ne

w York City, where Jim Kehler had opened an advertising agency on Fifth Avenue by 1915. In 1917, the couple gave up Deer Lick farm, their estate in Deerfield, north of Chicago, and for the next several years lived in apartments and hotels.

A friend, Marion Hofman, recalled: “Because both were temperamentally ‘high powered’ (my recollection of her description of both), they had separate flats (apartments) in N.Y., but I had no doubt of their love for each other.” Their independent arrangement ended when Kehler’s health failed in 1922. Ransom-Kehler nursed her husband through a long illness, from which he seemed to be recovering when he died unexpectedly of a heart attack on 19 June 1923 at their home in Chicago’s northern suburbs; he was only forty-seven years old. His death brought Ransom-Kehler, twice widowed, long-lasting grief.

In 1925, Ransom-Kehler became ill and went to Louisiana to recuperate. After she recovered, she was often on the move, maintaining the Vassar Club in New York City as her permanent address. A small income gave her freedom to travel widely as a lecturer, speaking on child psychology, philosophy, the role of women in modern life, interior design, comparative religion, and the Bahá’í Faith.

Ransom-Kehler became a Bahá’í in May 1921, but her first documented encounter with the Faith occurred a decade earlier, when she met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in London on September 13, 1911. She mentioned the meeting in passing in her diary twenty years later, but no account of the occasion has been discovered. She may have learned of the Bahá’í Faith when she lived in Paris, where the new religion gained attention in expatriate and artistic circles around the turn of the century. May Maxwell, the focal figure in the early Bahá’í community in Paris, was a friend of Ransom-Kehler’s in the 1920s and 1930s, but an earlier connection between the two women has not been established.

Shortly after becoming a Bahá’í, Ransom-Kehler gained recognition as a Bahá’í speaker, writer, and administrator. In 1924–25 she served as secretary of the Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of Chicago—the local governing council —until ill health led her to leave for Louisiana. In July 1925 she chaired a session of the Bahá’í Congress held in conjunction with the national Bahá’í convention held at Green Acre, the Bahá’í school and conference center in Eliot, Maine; the topic of the evening was “The Economic Foundation of World Brotherhood.” She traveled and lectured on a variety of Bahá’í topics, speaking at a series of meetings in Montreal in mid-1925 and, later that year, addressing meetings of the National Association of Teachers in Colored Schools held in Durham, North Carolina. In New York, between 1926 and 1929, her speaking commitments frequently took her to Harlem, where she assisted with a regular interracial “fireside,” as presentations on the

Bahá’í Faith involving questions and discussion are called.

Ransom-Kehler established a reputation as one of the most outstanding Bahá’í speakers of the era. Her talks were described by a contemporary as “well organized, strongly presented, intellectually based.” Her writing was equally well received. She contributed articles to Bahá’í periodicals (among which were forty-six for The Bahá’í Magazine: Star of the West, including three on Bahá’í administration written at Shoghi Effendi’s request).

Early in 1926 Ransom-Kehler went on pilgrimage to the Bahá’í holy places in Mandatory Palestine. She was deeply touched by the authority, majesty, and youth of Shoghi Effendi and by the immense burdens he carried as head of the Bahá’í Faith; in particular she found him “nearly crushed” by a “stupendous avalanche of personal correspondence,” much of it from American Bahá’ís who wrote to air their dissatisfactions and complaints against individuals and spiritual assemblies.

After her pilgrimage, at Shoghi Effendi’s urging, she wrote a letter to the delegates gathered at the annual Bahá’í convention for the United States and Canada in which she described his work poignantly and conveyed a plea for unity that he had expressed to her. “What we need is not so much devotion to the Cause for this has been already abundantly proven,” she quoted Shoghi Effendi as having told her, “but this love . . . must be translated into love for one another. If this Cause cannot unite two individuals how can we expect it to unite the world?” Moreover, the “greatest lesson” for the American Bahá’ís to learn, he had told her, was “spontaneous, full and hearty support of the Spiritual Assemblies,” not because their decisions are “sacrosanct” or “infallible,” but because such support is “‘the only means by which the Cause can be safeguarded.'” In response to this letter, the delegates passed a resolution intended to stem the tide of negative correspondence from American Bahá’ís to Shoghi Effendi.

On returning from her pilgrimage in the spring of 1926, Ransom-Kehler intensified the pace of her activities. She conducted study classes in New York City for hundreds of inquirers attracted by the professional lecturer Orcella Rexford, who gave series of talks on topics of current interest and invited her audiences to separate Bahá’í meetings. Ransom-Kehler’s efforts met with such success that the New York Bahá’ís were encouraged to lease a larger center and launch an ambitious teaching program—involving “a progressive presentation of the Bahá’í Cause, a public forum with invited speakers, and fortnightly meetings addressed by leaders of various liberal and humanitarian movements reflecting the Bahá’í principles”—in which Ransom-Kehler herself participated. She also helped with a series of world unity conferences organized by the American Bahá’í community in 1926–27.

In 1929, the year that her daughter graduated from Vassar, Ransom-Kehler made a trip to the West Indies, concentrating on Barbados. She went to the Pacific Coast in 1930, spending almost a year visiting cities in California, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia. In 1931 she embarked on an extended world tour as a lecturer and an advisor to Bahá’í communities on the emerging pattern of Bahá’í administration. Her itinerary included Hawaii, Japan, China, Australia, New Zealand, Java, Singapore, Burma, and India.

Ransom-Kehler made a deep impression wherever she traveled. Despite her feelings of inadequacy as a Bahá’í teacher, she found that the Bahá’ís she visited always wanted her to remain longer than planned. She usually had to extend her stay beyond the departure date that she had originally set.

Even though her schedule was often hectic, Ransom-Kehler managed to keep detailed accounts of her travels. Her diaries reveal a truly elegant, upright soul. Because of her quick temper, intellect, and wit, she often restrained her tongue, revealing her thoughts to her diary instead; but these same qualities made her an ardent defender of her beliefs, which included an uncompromising commitment to the advancement of women. She relied on prayer with implicit faith and told friends that she was as emotive with God as she was with people. She said that, when she prayed, “they know there’s something doing in Heaven.”

She loved literature and took comfort in remembered fragments of old poems, which one finds sprinkled throughout her letters and diaries. She was a passionate lover of beauty with eclectic tastes and a deep interest in the cultures she encountered on her journeys. Her diaries and letters abound with observations of cultural practices, art, and food. She seemed especially taken with Japanese culture and customs. One of her “Letters Home” published in the Bahá’í Magazine was devoted entirely to the beauty of the mountain city of Nikko, with its historic temples and shrines, which she found “elegant, sumptuous, magnificent.” Her contact with the Maori of New Zealand left her with lasting impressions of “a nation of poets and artists” who brought “the impress of beauty” to virtually “everything they touched”—sometimes with delicacy, at other times with “an opulent vigor of detail . . . that bespeaks a robust and dramatic taste.”

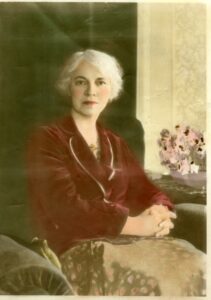

Ransom-Kehler’s appreciation of beauty and harmony extended to her own grooming, from her carefully waved hair to her thoughtfully chosen accessories. She was, to the end of her life, an elegant dresser who noted in her diary the ensembles she wore for lectures and social events. The mountains of luggage that she took on her historic journeys included sable wraps, chinchilla coats, and Chanel ensembles, as well as souvenirs she purchased when she occasionally found time in her busy schedule for shopping. Packing before departure was a lengthy ordeal. Even as a lone passenger on a freighter bound from China to Australia, sailing through tropical seas, she always dressed for dinner. She once told a friend “that if she were invited to Buckingham Palace ‘tomorrow,’ she had the clothes.” Yet she was also down to earth and capable of adapting to difficult and dangerous conditions.

While Ransom-Kehler was in India in May 1932, Shoghi Effendi cabled her, asking her to visit Haifa in preparation for a special assignment in Iran. She was “thunderstruck” by this request. After years of exhausting travel, Ransom-Kehler did not see herself as a standard-bearer; rather, she described herself as “a poor, feeble, old woman.” She had no idea of the high regard in which she was held by Shoghi Effendi, who later described her as an “INVALUABLE COLLABORATOR,” an “UNFAILING COUNSELOR,” and an “ESTEEMED AND FAITHFUL FRIEND.”

In Haifa, Ransom-Kehler learned that her mission to Iran was twofold. As the representative of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States and Canada, North America’s Bahá’í governing council, and on behalf of Sho

ghi Effendi, she was to petition Reza Shah Pahlavi (reigned 1925–41) to remove the ban on the entry and distribution of Bahá’í literature in Iran and also to secure the lifting of all the limitations that had for years been imposed on the Iranian Bahá’í community. Since gaining sovereignty in 1925, Reza Shah had instituted social, educational, and legal reforms that had raised the hopes of the hard-pressed Bahá’ís. In 1929 Shoghi Effendi had encouraged the Iranian Bahá’ís to seek permission to publish and distribute literature, but they had not succeeded in gaining the government’s approval. By 1932 the government still proved intransigent, and periodic recurrences of anti-Bahá’í violence—arrests, murders, expropriations, and sacking of properties—continued to plague the Bahá’í community. Shoghi Effendi found in Ransom-Kehler the strength, courage, and audacity that he hoped would persuade the shah to emancipate the Bahá’ís. In addition, Shoghi Effendi gave her a second mission: to instruct the Iranian Bahá’ís in the proper functioning of Bahá’í administration.

During Ransom-Kehler’s short stay in Haifa, Shoghi Effendi personally tutored her in an intensive study of Islam and briefed her about Iran. As always, she learned well, earning the appellation Mu’allimih (Teacher) given her by Bahíyyih Khánum, Bahá’u’lláh’s daughter. As Ransom-Kehler was about to leave Haifa for Iran, Bahíyyih Khánum—who had never returned to the homeland she left as a child—told her to greet every Bahá’í on her (Bahíyyih Khánum’s) behalf and to enter Tehran in her name. Bahíyyih Khánum died on July 15, 1932, a few weeks after Ransom-Kehler reached Tehran.

Ransom-Kehler traveled widely throughout Iran for more than a year. She was deeply touched by the loving welcome the Bahá’ís gave her in every town and village she visited. Her arrival at the village of Saysán, for example, was “a triumphal progress so extravagant that it will remain forever, not an episode, but an acute emotional experience.” The experience provided a new appreciation of unity: the real meaning of Bahá’í solidarity suddenly penetrated me. Here were Persians speaking Turkish, fixed in a tiny town in the mountains of Adhirbáyján, and I . . . ; but we were bound together by ties “more lasting than bronze and higher than the exalted site of the Pyramids.” For knowledge of the coming of Bahá’u’lláh and knowledge of His All-enfolding Covenant is not a question of locality, education or preferment but an unshakable spiritual reality that welds those who know it into an indissoluble human brotherhood. Here is a true solidarity that can withstand all the forces of disruption in the universe.

Ransom-Kehler’s interactions with the Iranian government were far less rewarding, however. Even before the end of 1932, initial hopes had been dashed, and some hint of the fruitlessness of the primary goal of her mission had become apparent. Soon after she reached Tehran, bearing with her a written petition to the shah from the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States and Canada, she gained—remarkably—an audience with Abdul Hossein Khan Teymourtash, Reza Shah’s first Minister of Court and closest political advisor. Teymourtash assured her that the ban on Bahá’í literature would be lifted immediately. When she asked if she could have her Bahá’í books mailed to her, he gave her firm assurance that she could. She cabled the National Assembly several days later, on 20 August 1932, “Mission successful.” But apparent success soon gave way to frustration. The ban remained in effect, and customs officials refused to allow her books into the country. She was unable to meet with Teymourtash again. He fell from his eminent position, being dismissed by Reza Shah late in 1932 and then arrested, and died in prison in October 1933.

Ransom-Kehler addressed seven long, incisive letters to the shah and tolerated many sessions with officials whose insincerity was all too evident to her. She knew that the shah was probably never apprised of the contents of her letters. She received no reply.

Although she was unable to win basic freedoms for the Iranian Bahá’ís, Ransom-Kehler’s determination was unwavering. “I have fallen, though I never faltered,” she wrote in one of the final entries in her diary. “Months of effort with nothing accomplished is the record that confronts me. If anyone in future should be interested in this thwarted adventure of mine, he alone can say whether near or far from the seemingly impregnable heights of complaisance and indifference, my tired old body fell. The smoke and din of battle are to-day too dense for me to ascertain whether I moved forward or was slain in my tracks.”

Even as her mission in Iran came to an end, Ransom-Kehler was full of plans for the future: she would return to India, and Shoghi Effendi had also asked her to go to Europe. But her efforts to obtain the emancipation of the Bahá’ís in Iran had worn her down. Because she was an open, astute, highly sensitive, completely frank person, she found it frustrating to deal with authorities who repeatedly said one thing and did another. She was fifty-seven years old and suffered from sciatica and other ailments. She had traveled tirelessly throughout Iran for over a year; indeed, she had been traveling almost continuously since 1929. She was malnourished, for health problems prevented her from eating much of the food she was offered, and had been adversely affected by the harsh climate. She had endured periods of extreme hardship. Once, for example, stranded by floods in rural northern Iran, her party “spent three nights, cold, bedraggled, covered with fleas, without removing our clothes, half suffocated with wood-smoke, on flimsy cots.” Although the group remained “remarkably cheerful and happy,” Ransom-Kehler was so tired that, when they reached their destination, she “rudely left them to bathe and sleep the clock around.”

Thus, exhausted and weakened, she left Tehran, planning to visit several cities in the southern part of Iran before leaving the country. In Isfahan she maintained her usual busy schedule until she suddenly fell ill on October 9, 1933 after a full day of activities. Exposed to smallpox, possibly by cuddling a child recovering from the disease, she had no physical resistance. She died two weeks later, on October 23.

The Bahá’ís of Isfahan arranged an impressive funeral. Ransom-Kehler was buried in the Bahá’í cemetery near the graves of two distinguished brothers, Mírzá Muhammad Hasan and Mírzá Muhammad Husayn, executed for their faith in 1879, whom Bahá’u’lláh had designated the King of Martyrs and the Beloved of Martyrs. Shortly before becoming ill, she had paid an emotionally charged visit to the cemetery and had prayed and wept at these graves.

Horace Holley, writing on behalf of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States and Canada, compared the last year of Ransom-Kehler’s life to “a wave whose concentrated force breaks upon a rocklike obstacle, then recedes to be gathered into the body of the sea. While the obstacle remains, the force has not been spent in vain. In future years the effect of this valiant faith will be fully disclosed.”

A week after Ransom-Kehler’s death, Shoghi Effendi cabled the North American Bahá’ís a touching tribute:

“KEITH’S PRECIOUS LIFE OFFERED UP SACRIFICE BELOVED CAUSE IN BAHÁ’U’LLÁH’S NATIVE LAND. ON PERSIAN SOIL FOR PERSIA’S SAKE SHE ENCOUNTERED CHALLENGED AND FOUGHT FORCES OF DARKNESS WITH HIGH DISTINCTION, INDOMITABLE WILL, UNSWERVING EXEMPLARY LOYALTY. MASS OF HER HELPLESS PERSIAN BRETHREN MOURN SUDDEN LOSS THEIR VALIANT EMANCIPATOR.” Describing himself as “SORROW-STRICKEN” at her loss, Shoghi Effendi called her the “FIRST AND DISTINGUISHED” American Bahá’í martyr and appointed her a Hand of the Cause of God, the first woman and only the second westerner to achieve that distinction: “INTERNATIONAL SERVICES ENTITLE HER EMINENT RANK AMONG HANDS OF CAUSE OF BAHÁ’U’LLÁH.” He sent a representative, Abu’l-Qasim Faizi, to lay a wreath on her grave and to tell the Bahá’ís of Iran that Ransom-Kehler had “solidly welded the Bahá’ís of the East and the West” and had “glorified and exalted God’s cause.”

In 1940, Shoghi Effendi named her, along with May Maxwell and the indefatigable international teacher Martha Root, as one of “three heroines of the Formative Age of the Faith of Bahá’u’lláh” to whom the Bahá’ís owe a debt of gratitude that “future generations will not fail to adequately recognize.” Writing in God Passes By, his history of the first hundred years of the Bahá’í Faith, 1844–1944, he mentioned several times “the fearless and brilliant Keith Ransom-Kehler,” citing her “tenacity and self-sacrifice” as one of the “[m]any and diverse forces” that urged the North American Bahá’í community to “strong action” during the first Seven Year Plan for expansion (1937–44), which brought the Faith’s first century to a close.

Editor’s Note:

A cenotaph in her honor is located in the Saint Joseph City Cemetery, Saint Joseph, Michigan.

Source:

Ruhe-Schoen, Janet “Keith Bean Ransom-Kehler” Bahá’í Encyclopedia Project. bahai-encyclopedia-project.org

Images:

©Baha’i Chronicles

Bahá’i World Archives

Funeral image is from the personal archive of Mrs. Nura (Faridian) Steiner