‘Abdu’l-Bahá Abbas

‘Abdu’l-Bahá Abbas

Born: May 23, 1844

Death: November 28, 1921

Place of Birth: Tehran, Iran

Location of Passing: Haifa Israel

Burial Location: Shrine of the Báb on Mount Carmel, Haifa, Israel

Abbás Effendi, the eldest of three surviving children of Bahá’u’lláh and His wife Ásíyyih Khánum, was born in Tehran, Iran, on May 23, 1844, the day on which the Báb declared His mission in Shiraz. ‘Abbás Effendi—who, after Bahá’u’lláh passed away, added to His given name the title ‘Abdu’l-Bahá (the Servant of the Glory)—was named for His paternal grandfather, ‘Abbás, known as Mírzá Buzurg Núrí. A member of a well-established and distinguished family, Mírzá Buzurg had served the government in many capacities including the governorship of Burujird and Luristan in western Iran, and was much admired for his accomplishments as a calligrapher and respected as a high government official. He was a friend of the famous prime minister, poet, and scholar Mírzá Abu’l-Qásim of Faráhán, the Qá’im Maqám (whose title means “vice-regent”).

Bahá’u’lláh, known in His youth as Mírzá Husayn-‘Alí, was Mírzá Buzurg’s eldest surviving son by his second wife, Khadíjih Khánum. Showing no interest in political life and not desiring a position at court, Bahá’u’lláh spent His time dispensing charity to the poor and discussing philosophical and theological matters with a circle of His father’s friends, impressing His interlocutors with the depth of His understanding of abstruse issues. For His charitable works, He acquired the appellation “Father of the Poor.” He became a follower of the Báb in 1844.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s mother, Ásíyyih Khánum, who was known as Navváb, came from a noble family of Mazandaran. She and Bahá’u’lláh married in 1835 and had seven children, three of whom survived to adulthood.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá spent His early years in an environment of privilege, wealth, and love. The family’s Tehran home and country houses were comfortable and beautifully decorated. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and his younger full siblings—a sister, Bahíyyih, and a brother, Mihdí had every advantage their station in life could offer.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s childhood was soon marked, however, by the persecution of the Bábís, of whom His father was one of the most prominent. In August 1852 three young Bábís, maddened by grief over the execution of the Báb two years earlier, made a misguided, failed attempt on the life of the shah. Bahá’u’lláh, who had no part in the assassination plot, was arrested, as were large numbers of other Bábís, and imprisoned in a subterranean dungeon known as the Síyáh-Chál (Black Pit) in Tehran. Bahá’u’lláh’s home was looted, and His family had to seek shelter in a rented house in a back alley.

Only eight years of age, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, who had recently recovered from a potentially fatal bout of tuberculosis, now had to endure separation from His beloved father, physical deprivation, insults, and even attacks by the children of the neighborhood. Sixty years later He recollected one such episode, when His mother had sent Him to His aunt’s house for a little money to buy food for the family: “On my way home someone recognized me and shouted: ‘Here is a Bábí’; whereupon the children in the street chased me. I found refuge in the entrance to a house . . . There I stayed until nightfall, and when I came out, I was once again pursued by the children who kept yelling at me and pelted me with stones . . . When I reached home I was exhausted. Mother wanted to know what had happened to me. I could not utter a word and collapsed.”

A visit to the dungeon where His father and a number of other Bábís were held etched itself deeply in ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s memory: “We entered a small, narrow doorway, and went down two steps, but beyond those one could see nothing. In the middle of the stairway, all of a sudden we heard His blessed voice: ‘Do not bring him in here’, and so they took me back. We sat outside, waiting for the prisoners to be led out. Suddenly they brought the Blessed Perfection [Bahá’u’lláh] out of the dungeon. He was chained to several others. What a chain! It was very heavy. The prisoners could only move it along with great difficulty. Sad and heart-rending it was.”

Bahá’u’lláh was released after four months, unlike many of His fellow prisoners, who were executed or who succumbed to the deplorable conditions in the dungeon. His remaining lands and possessions had been confiscated, and He received word almost immediately that He and His family had been banished from Iran. Bahá’u’lláh chose to go to Iraq, then a province in the Ottoman Empire. The exiles set out for Baghdad on January 12, 1853. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá would never see His native land again.

The long winter journey from Tehran to Baghdad was hard on the party, which, having been given insufficient time to prepare, was inadequately equipped. The months of travel on treacherous roads over high mountains were particularly trying for the children; for Navváb, who was pregnant; and for Bahá’u’lláh, released from prison in debilitated condition just a month earlier. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, according to His sister, suffered from frostbite. The family also grieved over separation from Mihdí, the youngest child, who had not been well enough to travel. When Bahá’u’lláh and His family reached Baghdad on April 8, 1853, they were ill and exhausted.

The long winter journey from Tehran to Baghdad was hard on the party, which, having been given insufficient time to prepare, was inadequately equipped. The months of travel on treacherous roads over high mountains were particularly trying for the children; for Navváb, who was pregnant; and for Bahá’u’lláh, released from prison in debilitated condition just a month earlier. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, according to His sister, suffered from frostbite. The family also grieved over separation from Mihdí, the youngest child, who had not been well enough to travel. When Bahá’u’lláh and His family reached Baghdad on April 8, 1853, they were ill and exhausted.

Baghdad proved no safe harbor. Dissension within the small community of Bábí exiles caused Bahá’u’lláh to leave Baghdad in April 1854, without telling even His family where He planned to go. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, then ten years old, endured another painful separation from His father, this time for two full years, during which Bahá’u’lláh lived in seclusion in the mountains of Kurdistan. Bahá’u’lláh’s return to Baghdad in 1856 began a period of relative stability and comfort for His family and of resurgence for the Bábí community, of which Bahá’u’lláh was generally recognized as the leader.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá attended no school during the Baghdad years, but, inspired and instructed by Bahá’u’lláh, He read avidly and memorized many of the works of the Báb. He also began to write, composing a commentary on a hadith (tradition)—”I was a Hidden Treasure”—attributed to the Prophet Muhammad that shows, in the words of Bahá’í historian Hasan Balyuzi, “profound knowledge, striking mastery of language, and rare qualities of mind, but above all . . . the most profound understanding.

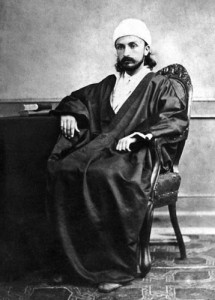

While still in His teens, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá became His father’s ambassador, His shield, and His amanuensis, transcribing some of Bahá’u’lláh’s writings, including the Kitáb-i-Íqán (Book of Certitude). On His father’s behalf He began to assume the burden of negotiations with government authorities in Baghdad. When Bahá’u’lláh was summoned to the Ottoman capital, Constantinople (Istanbul), in 1863, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá played a principal role in making arrangements for the difficult journey across Iraq and Anatolia, which took more than three months. “‘Abdu’l-Bahá was then a youth of nineteen, handsome, gracious, agile, zealous to serve, firm with the wilful, generous to all,” Balyuzi writes. “He strove hard to make the toil of a long journey less arduous for others. At night He was among the first to reach the halting-place, to see to the comfort of the travellers. Wherever provisions were scarce, He spent the night in search of food. And at dawn He rose early to set the caravan on another day’s march. Then the whole day long He rode by the side of His Father, in constant attendance upon Him.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s role became even more prominent in the subsequent stages of the family’s banishment—first during their four-month-long stay in Constantinople; then in Adrianople (Edirne), where they lived for more than four years; and finally in the prison city of Acre in Palestine, where the Ottoman authorities imprisoned them for forty years. After Bahá’u’lláh publicly proclaimed His mission in Adrianople in 1867, He withdrew from the general public, leaving ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to manage the affairs of the family and of the Bahá’í exiles. Thus ‘Abdu’l-Bahá became His father’s representative in all matters except those internal to the Bahá’í community.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá became widely known for qualities that the renowned British orientalist Edward G. Browne enumerated after meeting and conversing with Him in Acre in 1890: “One more eloquent of speech, more ready of argument, more apt of illustration, more intimately acquainted with the sacred books of the Jews, the Christians, and the Muhammadans, could, I should think, scarcely be found even amongst the eloquent, ready, and subtle race to which he belongs. These qualities, combined with a bearing at once majestic and genial, made me cease to wonder at the influence and esteem which hThe years in Acre were filled with difficulties and afflictions. While bearing weighty responsibilities, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá witnessed the death of His younger brother, Mihdí, and the suffering of the other exiles. Growing to full maturity during this period of tribulations, He went about the business of life, maintaining His devotion to the Bahá’í Cause, His determination to serve, His essential optimism and sense of humor. In 1872, shortly after having been released from more than two years of harsh confinement in the citadel of Acre, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, at the urging of Bahá’u’lláh, married Munírih Khánum, whose father had been a distinguished early Bábí from Isfahan. Over the years, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and Munírih Khánum had nine children—seven daughters and two sons; only four of their children, all daughters, survived to adulthoode enjoyed even beyond the circle of his father’s followers.”

As early as the Adrianople years (December 1863–August 1868), Bahá’u’lláh fully revealed to His close disciples ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s stature as His main support and most trusted servant. In the Tablet of the Branch (Súriy-i-Ghusn), written in Adrianople, Bahá’u’lláh extols His eldest son as the “Branch of Holiness”: “Render thanks unto God, O people, for His appearance; for verily He is the most great Favor unto you, the most perfect bounty upon you; and through Him every mouldering bone is quickened. Whoso turneth towards Him hath turned towards God, and whoso turneth away from Him hath turned away from My Beauty, hath repudiated My Proof, and transgressed against Me.”

Next to the Báb and Bahá’u’lláh, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá occupies the highest station in the Bahá’í Faith. In the Kitáb-i-Aqdas (Most Holy Book), Bahá’u’lláh enjoins the Bahá’ís to turn to “Him Whom God hath purposed, Who hath branched from this Ancient Root” and to “refer ye whatsoevr ye understand not in the Book to Him Who hath branched from this mighty Stock.” In these texts, in the Tablet of the Branch, and in the Book of the Covenant (Kitáb-i-‘Ahd), which constitutes His Will and Testament, Bahá’u’lláh establishes ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s authority as the Center of the Covenant (Bahá’u’lláh’s Covenant being the means by which He provided for the succession of leadership and the interpretation of His teachings after His passing).

Abdu’l-Bahá’s authority and His role, however, are not comparable to Bahá’u’lláh’s. On the basis of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s own numerous statements, which are “no less emphatic and binding” than Bahá’u’lláh’s, Shoghi Effendi—’Abdu’l-Bahá’s eldest grandson and His successor as Head of the Bahá’í Faith—makes it clear that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, “though the successor of His Father, . . . does not occupy a cognate station” and is not a Messenger of God.10 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá declares: “This is . . . my firm, my unshakable conviction. . . . The Blessed Beauty [Bahá’u’lláh] is the Sun of Truth, and His light the light of Truth. The Báb is likewise the Sun of Truth, and His light the light of Truth . . . My station is the station of servitude—a servitude which is complete, pure and real, firmly established, enduring, obvious, explicitly revealed and subject to no interpretation whatever . . . I am the Interpreter of the Word of God; such is my interpretation.”

Bahá’ís see ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, in the words of Shoghi Effendi, as “the stainless Mirror” of Bahá’u’lláh’s light, “the perfect Exemplar of His teachings, the unerring Interpreter of His Word, the embodiment of every Bahá’í ideal, the incarnation of every Bahá’í virtue.” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá is “the ‘Mystery of God’—an expression by which Bahá’u’lláh Himself has chosen to designate Him, and which . . . indicates how in the person of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá the incompatible characteristics of a human nature and superhuman knowledge and perfection have been blended and are completely harmonized.”

Bahá’ís see ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, in the words of Shoghi Effendi, as “the stainless Mirror” of Bahá’u’lláh’s light, “the perfect Exemplar of His teachings, the unerring Interpreter of His Word, the embodiment of every Bahá’í ideal, the incarnation of every Bahá’í virtue.” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá is “the ‘Mystery of God’—an expression by which Bahá’u’lláh Himself has chosen to designate Him, and which . . . indicates how in the person of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá the incompatible characteristics of a human nature and superhuman knowledge and perfection have been blended and are completely harmonized.”

Despite numerous written and oral statements Bahá’u’lláh had made about ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s future station as His successor, as the Head of the Bahá’í community, and as the authorized interpreter of the sacred writings, the succession of authority after Bahá’u’lláh’s passing in May 1892 was turbulent. Mírzá Muhammad ‘Alí, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s younger half-brother, soon challenged His position. The terms of the Kitáb-i-Aqdas and of Bahá’u’lláh’s Will and Testament—which honored Mírzá Muhammad ‘Alí but gave precedence to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá—were entirely clear. But those who trusted Mírzá Muhammad ‘Alí as Bahá’u’lláh’s son found their loyalties tested. In the ensuing climate of confusion, a number of Bahá’ís, among them many members of Bahá’u’lláh’s family and some outstanding Bahá’ís in Iran and elsewhere, accepted Muhammad ‘Alí’s claims. Their adherence to him precipitated a conflict that lasted for the lifetime of his generation.

Not even Muhammad ‘Alí’s partisans could deny that Bahá’u’lláh had named ‘Abdu’l-Bahá the Center of the Covenant, empowering Him to lead the Bahá’í community. Yet Mírzá Muhammad ‘Alí and his band of followers violated the provisions of Bahá’u’lláh’s testament and tried to usurp ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s authority. In Iran, Egypt, Europe, and America, Muhammad ‘Alí’s agents claimed that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had exceeded His rights and privileges, that He had arrogated to Himself powers that were not His, that He had wrongfully assumed the station of a Manifestation or Messenger of God, and that He had deprived His brothers of their birthright to be honored and cherished by the Bahá’ís. These attacks, although they posed a threat at first and caused ‘Abdu’l-Bahá great pain because of the disrepute they brought to the Bahá’í Faith, ultimately failed to produce a schism in the community or to damage its unity.

Frustrated in his designs to supplant ‘Abdu’l-Bahá as Head of the Bahá’í Faith, Mírzá Muhammad ‘Alí turned informer, providing false reports designed to poison the attitude of the authorities against his brother. In early 1900 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had begun the construction of the mausoleum of the Báb on Mount Carmel in Haifa. Mírzá Muhammad ‘Alí and his agents accused ‘Abdu’l-Bahá of building a fortress and preparing an uprising that would overthrow the Ottoman sultan, Abdülhamid II, and carve out a kingdom for Himself in Palestine. Alarmed by the charges, the suspicious government of the sultan, struggling against the centrifugal forces that were tearing the weakened Ottoman Empire apart, issued an order in August 1901 that confined ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and His brothers within the city limits of Acre. Later the government appointed a commission to investigate the charges. Having been influenced at the outset by the allegations of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s enemies, the commissioners collected rumors and insinuations but never discovered any incriminating facts, for none existed.

Rumors circulated in 1907–08 that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had been judged guilty and that He would be removed to Fezzan, an isolated desert region in Tripolitania where He would be certain to perish. However, the commission departed without taking action, and the turmoil in Constantinople, culminating in the Young Turk Revolution, distracted the sultan. In the summer of 1908 Abdülhamid was deprived of his autocratic powers and compelled to restore the Ottoman constitution and to release the empire’s religious and political prisoners. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was free.

Notwithstanding the tumult caused by Mírzá Muhammad ‘Alí, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá persevered in His designated duties as Head of the Bahá’í Faith and worked to overcome the obstacles it faced. His efforts to spread the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh bore fruit quickly, especially in Iran, where the Bahá’í community began to experience rapid growth, and in the West, particularly North America, where the first conversions to the Faith occurred in 1894–95.

During Bahá’u’lláh’s lifetime, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had helped to revive the shattered Bábí community in Iran and to foster its recognition of Bahá’u’lláh’s dispensation. After Bahá’u’lláh’s passing, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s constant care and encouragement led to a significant increase in the number of Bahá’ís in Iran. Because of His leadership and constant encouragement, the Iranian Bahá’ís established elected consultative bodies (later designated as Spiritual Assemblies), the first of which was elected in 1899 (See: Tehran.The Bahá’í Period to 1921). In the words of Century of Light, a survey of the history of the Bahá’í Faith against the background of the main political and social developments of the twentieth century: “The importance of the latter development alone would be impossible to exaggerate. In a land and among a people accustomed for centuries to a patriarchal system that concentrated all decision-making authority in the hands of an absolute monarch or Shí‘ih mujtahids, a community representing a cross section of that society had broken with the past, taking into its own hands the responsibility for deciding its collective affairs through consultative action.”

Equally significant was ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s direction and encouragement of the spread of the Bahá’í Faith in the West. In late 1898 and early 1899, the first groups of American Bahá’í pilgrims, including individuals residing in England and France, arrived in Acre. They and subsequent pilgrims received extensive instruction from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá that deepened their understanding of the religion they had recently embraced. In these early years ‘Abdu’l-Bahá began a vast correspondence with North American and European Bahá’ís, explaining the Bahá’í teachings, giving personal guidance, and steering the establishment of Bahá’í communities and embryonic administrative institutions.

As early as 1907, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá began moving His family to Haifa, where He had built a house at the foot of Mount Carmel. Work on the Báb’s sepulcher, midway up the mountain slope, had proceeded in spite of the investigations of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá carried out by the Ottoman government. In March 1909 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá placed the Báb’s remains in the Shrine, thereby establishing it as a place of pilgrimage second only to the Shrine of Bahá’u’lláh in Acre. Soon afterward, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá began residing in His house in Haifa, which then became the administrative center of the Bahá’í Faith.

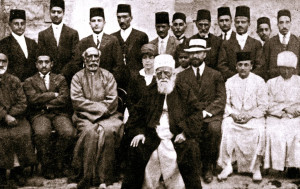

The years of confinement and opposition, added to the responsibilities He bore, seriously weakened ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s health. After He suffered several episodes of illness, His doctors urged a change in His surroundings. In August 1910 He sailed to Egypt, where He spent the next twelve months. There He met leading intellectuals; some Muslim divines; correspondents and editors of various newspapers and magazines; the Khedive (Turkish viceroy), Abbas Hilmi II; and the British consul-general Lord Kitchener (in effect, the ruler of Egypt at the time). In August 1911 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá traveled to Europe. He sailed to Marseilles, stopping at the French resort Thonon-les-Bains, on the shores of Lake Geneva, and in Geneva, Switzerland, before traveling to London. On 10 September 1911, from the pulpit of the City Temple, He gave a public address for the first time. His month-long stay in England, which included a brief visit to Bristol, was filled with public talks, meetings with the press, and interviews with individuals, setting a pattern that He would follow throughout His travels in Europe and North America. Next He went to Paris, where the first Bahá’í community in Europe had been established a decade earlier. He spent nine weeks there, returning to Egypt in early December to rest for the winter.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s second journey to the West was much more extensive in both duration (March 25, 1912 – June 17, 1913) and distance. He devoted most of this period to the North American continent. Arriving in New York on April 11, 1912, He traveled from the Atlantic to the Pacific, visiting a score of cities, among them Washington, Boston, Montreal, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Chicago (where He laid the cornerstone of the first Bahá’í House of Worship in the Western Hemisphere, Minneapolis, Denver, Salt Lake City, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. Everywhere He went, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá gave interviews to the press and addressed large and small gatherings in public halls, churches, universities, and private homes, proclaiming the principles of the Bahá’í Faith, stressing the need for religious and racial unity, equality of the sexes, and world peace.

In the course of these travels in North America, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá met people of all ranks and stations: high government officials, business magnates, artists, writers, politicians, scholars, clergy of various denominations, and derelicts in the Bowery. Among the individuals He met were David Starr Jordan, president of Stanford University; Rabbi Stephen S. Wise of New York City; the inventor Alexander Graham Bell; Jane Addams, the noted social worker; the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore, who was touring America at the time; Herbert Putnam, Librarian of Congress; the industrialist and humanitarian Andrew Carnegie; Samuel Gompers, president of the American Federation of Labor; the Arctic explorer Admiral Robert Peary; as well as hundreds of American and Canadian Bahá’ís, recent converts to the religion, whom He instructed and inspired and whose lives were permanently changed by their contact with Him. Many of the latter were women who, encouraged by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, would play an extraordinarily important role in spreading the Bahá’í Faith in North America and taking it to the far corners of the earth—participating in the building of its administrative institutions, establishing and teaching in Bahá’í schools, contributing to Bahá’í literature, and leaving their imprint on every facet of the development of the Bahá’í community at home and abroad.

In the course of these travels in North America, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá met people of all ranks and stations: high government officials, business magnates, artists, writers, politicians, scholars, clergy of various denominations, and derelicts in the Bowery. Among the individuals He met were David Starr Jordan, president of Stanford University; Rabbi Stephen S. Wise of New York City; the inventor Alexander Graham Bell; Jane Addams, the noted social worker; the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore, who was touring America at the time; Herbert Putnam, Librarian of Congress; the industrialist and humanitarian Andrew Carnegie; Samuel Gompers, president of the American Federation of Labor; the Arctic explorer Admiral Robert Peary; as well as hundreds of American and Canadian Bahá’ís, recent converts to the religion, whom He instructed and inspired and whose lives were permanently changed by their contact with Him. Many of the latter were women who, encouraged by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, would play an extraordinarily important role in spreading the Bahá’í Faith in North America and taking it to the far corners of the earth—participating in the building of its administrative institutions, establishing and teaching in Bahá’í schools, contributing to Bahá’í literature, and leaving their imprint on every facet of the development of the Bahá’í community at home and abroad.

During His sojourn in the United States, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá constantly emphasized in public addresses, private conversations, and written communications the importance of eradicating the racism deeply ingrained in American society. “God maketh no distinction between the white and the black,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá told a gathering in New York City. “God is no respecter of persons on account of either color or race. All colors are acceptable to Him, be they white, black, or yellow. Inasmuch as all were created in the image of God, we must bring ourselves to realize that all embody divine possibilities.”

Leaving New York on December 5, 1912, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá traveled to England, France, Germany, and Austria-Hungary. In Europe, as in North America, He spoke at private gatherings and public meetings and met prominent individuals such as Albert Wilberforce, archdeacon of Westminster; Annie Besant, president of the Theosophical Society; suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst; orientalists Edward G. Browne of Cambridge University and Arminius Vambery and Ignatius Goldziher of the University of Budapest; as well as two Qajar princes in exile, Mas‘ud Mirza Zillu’s-Sultan and his son Husayn Mirza Jalalu’d-Dawlih—both of whom, while serving as governors in Iran, had been responsible for persecuting and executing Bahá’ís, and both of whom now showed respect toward ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

Leaving New York on December 5, 1912, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá traveled to England, France, Germany, and Austria-Hungary. In Europe, as in North America, He spoke at private gatherings and public meetings and met prominent individuals such as Albert Wilberforce, archdeacon of Westminster; Annie Besant, president of the Theosophical Society; suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst; orientalists Edward G. Browne of Cambridge University and Arminius Vambery and Ignatius Goldziher of the University of Budapest; as well as two Qajar princes in exile, Mas‘ud Mirza Zillu’s-Sultan and his son Husayn Mirza Jalalu’d-Dawlih—both of whom, while serving as governors in Iran, had been responsible for persecuting and executing Bahá’ís, and both of whom now showed respect toward ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s travels in Europe and North America were a major factor in the spread of the Bahá’í Faith in the West, the proclamation of its principles, and the firm establishment of Bahá’í communities on the two continents. Moreover, in His addresses to Western audiences, both to Bahá’ís and the general public, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá demonstrated the application of His father’s teachings to many contemporary issues and problems.

Throughout His travels in Europe and North America, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá frequently spoke of the age-old prevalence of warfare, made infinitely more deadly by twentieth-century science, and of the need to “unlearn the science of war” and to create the social conditions and the international political instruments necessary to establish peace. “The greatest catastrophe in the world of humanity today is war,” He told an audience in Montreal in September 1912:

Europe is a storehouse of explosives awaiting a spark. All the European nations are on edge, and a single flame will set on fire the whole of that continent. Implements of war and death are multiplied and increased to an inconceivable degree, and the burden of military maintenance is taxing the various countries beyond the point of endurance. Armies and navies devour the substance and possessions of the people; the toiling poor, the innocent and helpless are forced by taxation to provide munitions and armament for governments bent upon conquest of territory and defense against powerful rival nations. There is no greater or more woeful ordeal in the world of humanity today than impending war. Therefore, international peace is a crucial necessity. An arbitral court of justice shall be established by which international disputes are to be settled. Through this means all possibility of discord and war between the nations will be obviated.

Less than two years later, a spark struck in Sarajevo ignited a conflagration that quickly spread beyond the European continent. From November 1914—when the Allied Powers declared war on the Ottoman Empire, which had joined Germany and Austria-Hungary—until September 1918, World War I virtually isolated ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Palestine from Bahá’í communities in the West and in the East. The Ottoman authorities, fearful of the growing hostility of the local population, imposed draconian measures of control on the Holy Land. The commander of Turkish troops on the Egyptian front, Cemal Paşa (Jamál Páshá), was hostile to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Provoked by the followers of Mírzá Muhammad ‘Alí, he threatened to crucify ‘Abdu’l-Bahá on Mount Carmel as soon as Ottoman victory was achieved. However, Cemal Paşa’s Egyptian campaign failed. He was defeated, forced to retreat in haste, and rendered unable to carry out his threat.

Through the war years, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá encouraged the Bahá’ís in the Jordan River valley and on the shores of the Sea of Galilee to plant crops. The wheat they produced was distributed to the needy population of Haifa, saving it from starvation. This humanitarian service was recognized by the British, who occupied Haifa at the end of September 1918. The British government knighted ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in April 1920 and showed Him extraordinary signs of admiration and respect.

While ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s contacts with the outside world were severed during the war, He continued to write, producing one of the most important works of His ministry: the fourteen letters known as the Tablets of the Divine Plan. Written in March–April 1916 and February–March 1917, these letters, or tablets (the English rendering of the Arabic alwáh, plural of lawh), became the charter for the expansion and spread of the Bahá’í Faith over the entire globe. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá entrusted the mission of initiating this expansion to the Bahá’ís of North America, to whom the Tablets of the Divine Plan were addressed.

The last three years of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s life were spent in correspondence with an ever increasing number of Bahá’í individuals and communities throughout the world, a correspondence that guided their efforts to establish an organizational framework for the Bahá’í Faith and provided inspiration for its expansion. His interaction with the renewed stream of pilgrims to the Bahá’í shrines in Acre and Haifa provided another instrument for deepening the understanding of recent converts and veteran Bahá’ís alike. Yet age, long years of imprisonment and exile, strenuous travels, and overwork had taken their toll. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá foresaw the approaching end. Six months before His passing, He wrote in a prayer: “‘O Lord! My bones are weakened, and the hoar hairs glisten on My head . . . and I have now reached old age, failing in My powers.’ . . . No strength is there left in Me wherewith to arise and serve Thy loved ones . . . O Lord, My Lord! Hasten My ascension unto Thy sublime Threshold . . . and My arrival at the Door of Thy grace beneath the shadow of Thy most great mercy.”

Shoghi Effendi states in appreciation of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s achievements that He had taken the Bahá’í Faith to the West; had disclosed its character and purpose before vast audiences in Europe and North America; had brought the mortal remains of the Báb to the Holy Land and enshrined them on Mount Carmel; had inspired the erection of the first Mashriqu’l-Adhkár of the Bahá’í world in Ashgabat (Turkmenistan) and had laid the cornerstone of the second in Wilmette, Illinois; and had routed the breakers of His father’s Covenant. “Through His [‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s] unremitting labors,” Shoghi Effendi states, “as reflected in the treatises He composed, the thousands of Tablets He revealed, the discourses He delivered, the prayers, poems and commentaries He left to posterity . . . , the laws and principles, constituting the warp and woof of His Father’s Revelation, had been elucidated, its fundamentals restated and interpreted, its tenets given detailed application and the validity and indispensability of its verities fully and publicly demonstrated.”

Throughout His ministry of twenty-nine years, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá labored to spread the Bahá’í Faith to every part of the world and fostered the development of the administrative institutions ordained by Bahá’u’lláh. Under His guidance there grew in Iran a network of Spiritual Assemblies that managed the affairs of communities, organized schools, provided for the sick and the orphans, promoted health measures, resolved conflicts among individuals, and engaged in teaching the Bahá’í Faith.

The establishment in Iran of Bahá’í schools, with particular concern for the education of girls, the improvement of individual standards of health, and the moral transformation of believers, which gradually gained them a reputation for integrity and trustworthiness, testified to the effectiveness of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s leadership. He encouraged the advancement of women, who began to participate in community activities and, in the decades after His passing, attained equality with men as members of Spiritual Assemblies, both local and national, in Iran.

Abdu’l-Bahá also inspired the spread of the Bahá’í Faith in the Caucasus and Russian Central Asia, where Ashgabat with its Temple, schools, and publications, unhampered by government restrictions, became a model Bahá’í community. Egypt, which had greatly benefited from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s sojourn in that country, also witnessed the growth of a Bahá’í community that included both Muslim and Copt converts as well as Iranians, Kurds, and Armenians. In Turkey, Ottoman Iraq, Tunisia, and even distant China and Japan, Bahá’í communities sprang up or were strengthened at ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s behest.

The continents of Europe and North America were the stage for ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s own teaching activities. The Bahá’í communities of Europe and North America, established entirely during His ministry, were a direct result of His unceasing efforts. He paid particular attention to the development of the Bahá’í Faith and its institutions in the United States and Canada and entrusted to the Bahá’ís of North America the task of carrying the teachings and spirit of Bahá’u’lláh to most of the rest of the world. In the last years of His ministry, at His urging and in response to His Tablets of the Divine Plan, the first Bahá’ís reached South America and Australia.

Although ‘Abdu’l-Bahá carried out many of His activities through personal contact with visitors and pilgrims and through His travels, He conducted most of His work through a vast and varied correspondence. The Bahá’í World Center currently holds nearly sixteen thousand of His letters to individuals and institutions. The writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá also comprise essays, poems, prayers, and books. It has been estimated that four-fifths of them are in Persian and the rest in Arabic, with a very few in Ottoman Turkish. The letters have been described as “masterpieces of Persian epistolary genre” that “are marked by directness, intimacy, warmth, love, humor, forbearance, and a myriad other qualities that reveal the exemplary perfection of His personality.”

Some of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s letters addressed to individuals deal with issues of general interest; transcending the personal, they constitute essays on a variety of themes. One of the most widely known is ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Tablet to August Forel, a Swiss scientist, in which ‘Abdu’l-Bahá discusses the nature of God and of human beings. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá also wrote to Bahá’í communities, offering guidance and inspiration to the recipients and to future generations. The Tablets of the Divine Plan, the charter for global expansion that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá addressed to the Bahá’ís of the United States and Canada, are preeminent in this category. They constitute a document of fundamental importance in the development of the Bahá’í world community, spelling out the steps in the global spread of the Faith and serving as the basis for all subsequent plans for growth. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá also wrote to organizations, such as the Central Organization for a Durable Peace at The Hague, and occasionally to newspapers, such as the Christian Commonwealth.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Will and Testament occupies a special place among His writings. Shoghi Effendi states that, like the Tablets of the Divine Plan, it is one of the charters of the Bahá’í order. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá composed its first section, and possibly the entire document, in the period between 1901 and 1908, when the Ottoman government, incited by Mírzá Muhammad ‘Alí and his followers, threatened ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s life. The document establishes the Bahá’í Administrative Order, Shoghi Effendi observes, and “may be regarded in some of its features as supplementary to no less weighty a Book than the Kitáb-i-Aqdas.” He points out that it creates the institution of the Guardianship; provides “measures for the election of the International House of Justice”; prescribes the obligations and responsibilities of the Hands of the Cause of God; provides for the protection of the Bahá’í Faith against disunity and schism; and summons the followers of Bahá’u’lláh “to arise unitedly to propagate His Faith, to disperse far and wide, to labor tirelessly and to follow the heroic example of the Apostles of Jesus Christ.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Will and Testament occupies a special place among His writings. Shoghi Effendi states that, like the Tablets of the Divine Plan, it is one of the charters of the Bahá’í order. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá composed its first section, and possibly the entire document, in the period between 1901 and 1908, when the Ottoman government, incited by Mírzá Muhammad ‘Alí and his followers, threatened ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s life. The document establishes the Bahá’í Administrative Order, Shoghi Effendi observes, and “may be regarded in some of its features as supplementary to no less weighty a Book than the Kitáb-i-Aqdas.” He points out that it creates the institution of the Guardianship; provides “measures for the election of the International House of Justice”; prescribes the obligations and responsibilities of the Hands of the Cause of God; provides for the protection of the Bahá’í Faith against disunity and schism; and summons the followers of Bahá’u’lláh “to arise unitedly to propagate His Faith, to disperse far and wide, to labor tirelessly and to follow the heroic example of the Apostles of Jesus Christ.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá wrote a large number of prayers (munáját), mostly in Persian and Arabic, with a few in Turkish. The “chief distinguishing quality” of these brief communions with God has been described as “the sustained and expanding expression of man’s experience of the Holy by means of poetic language.”

In addition to longer tablets, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá produced three monographs during the years when His responsibilities still allowed Him to devote time to book-length works: The Secret of Divine Civilization and A Traveler’s Narrative, both written during Bahá’u’lláh’s lifetime, and A Treatise on Politics. The Secret of Divine Civilization is the first of these major works. Written in 1875, addressed to the Iranian people, and published anonymously, it is an outstanding example of the application of Bahá’u’lláh’s principles to a specific situation: the modernization of Iran. Historian Amin Banani writes that, in this pioneer work, which anticipates and offers solutions to many problems that modernizing societies have faced, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá presents a coherent program for the regeneration of Persian society. The program is predicated on universal education and eradication of ignorance and fanaticism. It calls for responsibility and participation of the people in government through a representative assembly. It seeks to safeguard their rights and liberties through codification of laws and institutionalization of justice. It argues for the humane benefits of modern science and technology. It condemns militarism and underscores the immorality of heavy expenditures for armaments. It promulgates a more equitable sharing of the wealth of the nation.

The second of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s books, A Traveler’s Narrative, is a brief history of the Báb intended for a general audience. Written in or around 1886, it was translated into English by Edward G. Browne and published by Cambridge University Press in 1891. The third work, A Treatise on Politics, written in 1892–93, may be considered a sequel to The Secret of Divine Civilization; it has not been translated and is available only in the original Persian.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá approved for publication two compilations of His talks: Some Answered Questions and Memorials of the Faithful. Published in 1908, Some Answered Questions is a record of table talks on the spiritual teachings of the Bahá’í Faith and on some Christian subjects; the talks were given in response to questions posed by an American pilgrim, Laura Clifford Barney. Memorials of the Faithful, dating from 1915, is a series of spiritual portraits of more than seventy early Bahá’ís that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá presented to weekly gatherings of Bahá’ís in His home in Haifa.

Many of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s talks in Europe and America have been compiled in The Promulgation of Universal Peace: Talks Delivered by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá during His Visit to the United States and Canada in 1912; ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in London; ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Canada; and Paris Talks. These books contain a wealth of material and further amplify Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings on many contemporary problems, particularly those faced in the West.

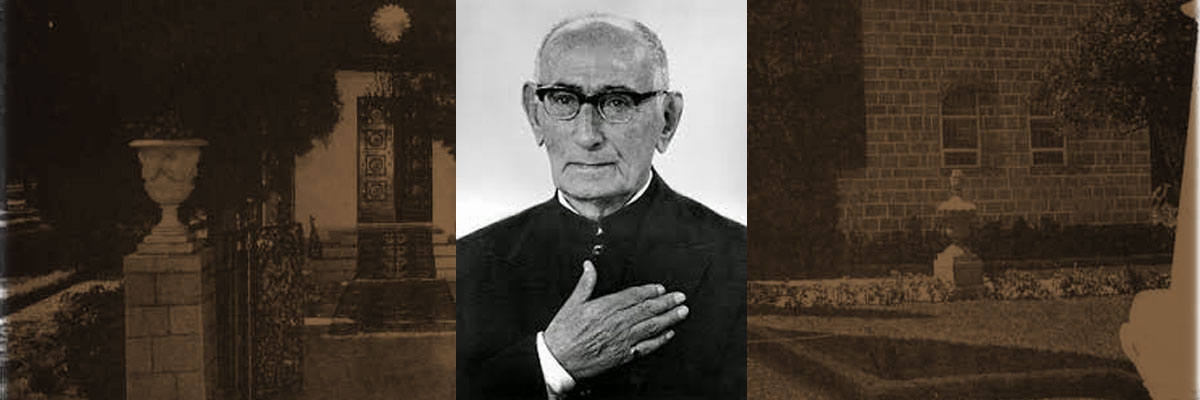

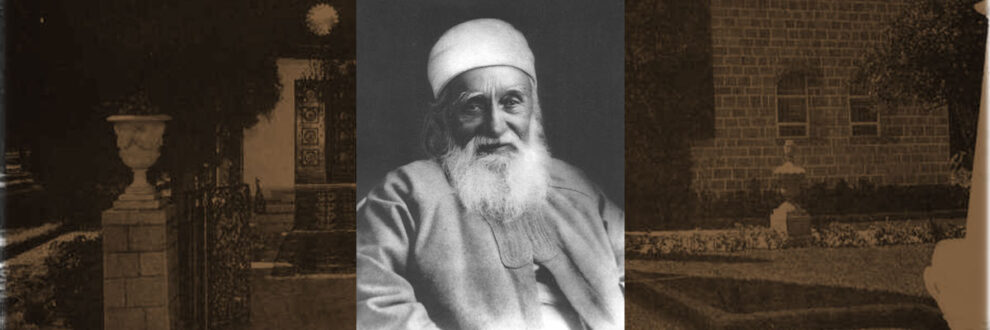

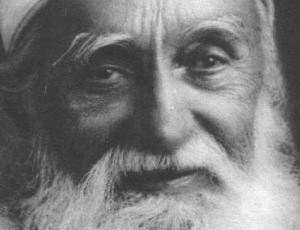

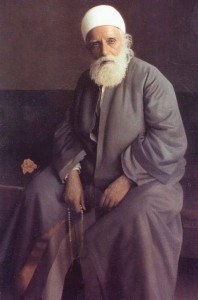

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s person made a deep impression on all who met Him. Friends and strangers, Europeans, Americans, and Asians testified to His gentleness and kindness, His welcoming smile, His exquisite courtesy, and His delightful sense of humor. Edward G. Browne of Cambridge University wrote after meeting ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in 1890:

Seldom have I seen one whose appearance impressed me more. A tall strongly-built man holding himself straight as an arrow, with white turban and raiment, long black locks reaching almost to the shoulder, broad powerful forehead indicating a strong intellect combined with an unswerving will, eyes keen as a hawk’s, and strongly marked but pleasing features—such was my first impression of ‘Abbás Efendí, “the master” (Áká) as he par excellence is called by the Bábís [i.e., the Bahá’ís]. Subsequent conversation with him served only to heighten the respect with which his appearance had from the first inspired me. . . . About the greatness of this man and his power no one who had seen him could entertain a doubt.

Horace Holley, an American who met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in France, felt the spirit that emanated from Him. “I yielded to a feeling of reverence,” Holley writes, “which contained more than the solution of intellectual or moral problems. To look upon so wonderful a human being, to respond utterly to the charm of His presence—this brought me continual happiness. . . . Patriarchal, majestic, strong, yet infinitely kind, he appeared like some just king that very moment descended from his throne to mingle with a devoted people.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s capacity for work, His disregard for personal comfort, His ability to endure hardship, His generosity, His love for children, His sense of humor, His concern for the poor and the sick, His love for nature and beauty, combined with an iron will, an unswerving devotion to truth and justice, and an all-consuming sense of duty toward the community entrusted to Him by Bahá’u’lláh, were characteristics noted by hundreds of observers.

Abdu’l-Bahá passed away in Haifa at the age of seventy-seven in the early hours of the morning on November 28, 1921. The funeral, held the next day and attended by thousands of mourners, was a spontaneous tribute to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s person. Representatives of the Catholic, Orthodox, and Anglican churches and of the Muslim, Jewish, and Druze faiths; officials, led by the British High Commissioner for Palestine and the governors of Jerusalem and Phoenicia; Arabs, Jews, Kurds, Turks, Europeans, and Americans followed the coffin up the slopes of Mount Carmel to the Shrine of the Báb, in one of whose chambers ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s mortal remains were laid to rest. His death marked the end of the Heroic or Apostolic Age of the Bahá’í Faith, which began with the Bab’s declaration on May 23, 1844, the date of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s birth.

Source:

Kazemzadeh, Firuz “Abdul Baha Abbas” Bahá’í Encyclopedia Project. baha’i-encyclopedia-project.org

Images:

Baha’i World Centre Archives

Shrine of the Báb photo taken by Caroline Lüdecke